Working families with kids in child care are struggling right now. Families know how expensive and difficult the child care system is to navigate.

Australians pay some of the highest child care costs in the world.

In fact, fees have increased more than 35% under the Liberals.

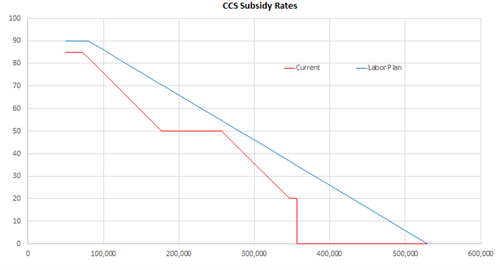

The way the current system is designed means many women actually lose money if they work more than three days a week.

That’s why Labor will reduce the cost of child care. Our policy will:

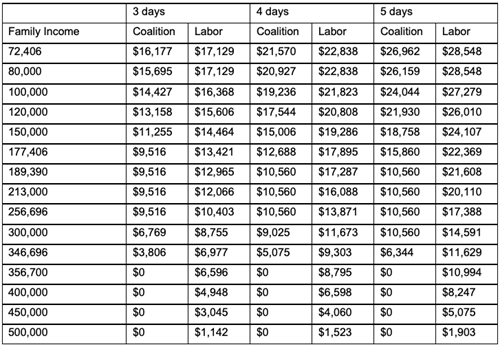

- Scrap the $10,560 child care subsidy cap which often sees women losing money from an extra day’s work;

- Lift the maximum child care subsidy rate to 90 per cent; and

- Increase child care subsidy rates for every family earning less than $530,000.

Labor will keep working to fix Australia’s broken child care system, which currently locks out more than 100,000 families because they just can’t afford it.

The Productivity Commission will conduct a comprehensive review of child care with the aim of implementing a universal 90 per cent subsidy for all families.

The ACCC will design a price regulation mechanism to shed light on costs and fees and drive them down for good. The ACCC will also examine the relationship between funding, fees, profits and educators’ salaries.

We will make it easier for mums, children and working families to get ahead. No family will be worse off.

Labor’s Cheaper Child Care policy will take the pressure off family budgets.

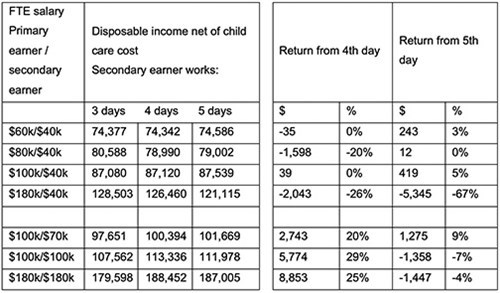

The current child care system is not designed to get everyone back to work. Many parents, across all income levels, want to go back to work or do more hours but find it just isn’t worth it because they don’t take home enough pay.

Many parents actually lose money if they work a fourth or fifth day.

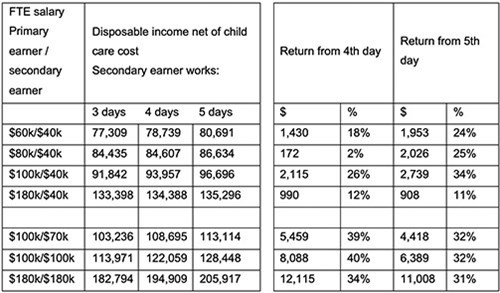

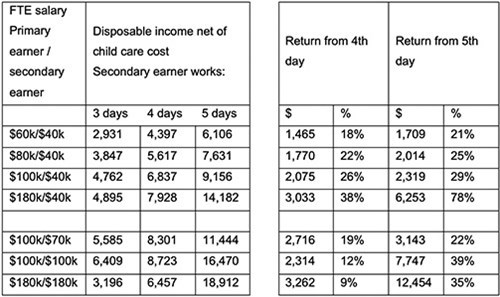

Labor’s Cheaper Child Care policy will remove these structural barriers that are holding second income earners – mostly women – back from work.

Cheaper child care is good for the economy, good for families and good for women.

Making child care more affordable will lift workforce participation and increase economic growth.

Economists have modelled how much the economy grows with more investment in child care.

KPMG estimated child care reform could generate between 160,000 and 210,000 additional working days a week – the equivalent of 30,000-40,000 full-time jobs.

Grattan Institute research concluded that women with young children will increase their hours of paid work by 13 per cent if the system is reformed to make child care cheaper.

These reports estimate that that reform of child care could generate GDP growth of between $4 billion and $11 billion per annum.

This is a fundamental microeconomic reform that will supercharge growth.

Labor’s Cheaper Child Care policy plan will deliver immediate support to families. And we also have a plan to bring child care fees under control.

We will ask the ACCC to conduct an in-depth market study into the Early Childhood Education and Care sector, to analyse the cost structures and cost drivers in the sector and report publicly with recommendations to better control costs. The ACCC will also examine the relationship between funding, fees, profits and educator salaries.

We will also undertake a root-and-branch analysis of child care through the Productivity Commission.

The review will give consideration to the possible transition to a universal 90 per cent subsidy for all families.

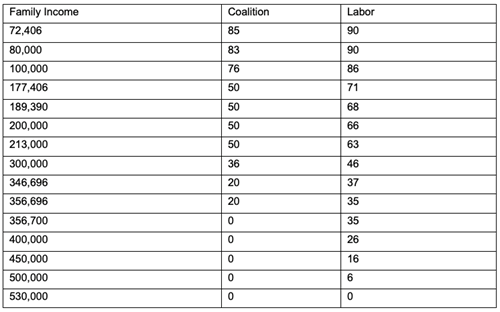

New subsidy rates

"Gross" Annual Child Care Subsidy

Assumes 52 weeks of care, $122 a day

Analysis shows Labor's child care plan rewards working families

Analysis by the Grattan Institute confirms Labor’s Cheaper Child Care plan will reward working families, and allow more second income earners, usually women, to work more and contribute to our economic recovery.

Current child care system

Labor's Cheaper Child Care Policy

Difference

Notes: Primary earner works full-time. Two children, both require child care. Every day of work for the second earner results in exactly one day of approved child care.

Source: Grattan analysis based on the ‘daily rate’ structure of Stewart (2018) and Ingles and Plunkett (2016).